In late August 2015, a new breast cancer study was released in JAMA (a prestigious medical journal). It was covered extensively in the media, generating much communication from patients, as often happens when new data hits the press. As women with breast cancer know, the flood of information, medical jargon, and numbers can be pretty overwhelming, and often times confusing.

In this case, the study involved patients with DCIS (ductal carcinoma-in-situ), the earliest form of breast cancer. The main, take-home message I believe should be derived from this study is that for women with DCIS, the overall long-term survival is excellent: 97-98%. This is good news, and all women with DCIS should keep this point in the forefront of their minds.

And there is more good news. Because there have been so many advances in the care and treatment of breast cancer in general—not just DCIS—there are more options than ever before in taking care of women with breast cancer. As surgeons and oncologists, our job is to decide which options are medically appropriate and then help a patient decide which is best for her as an individual: lumpectomy or mastectomy? Mastectomy or bilateral mastectomy? Chemotherapy or hormonal therapy? Or both? It’s not easy to navigate these pathways, but with the right guidance and the right team of doctors, the outcomes are usually very good, and the results from the JAMA study verify this fact.

But when the JAMA study came out, the women who called my office did not feel this message of optimism. Mostly, there was confusion and anxiety. And there were two specific concerns that I heard over and over again that I want to shed light on in a way that I hope is helpful and clarifying.

Here are the main questions I received and my answers:

1) I had a mastectomy for DCIS. Do the results of this study mean I was “overtreated” and would have had the same outcome with lumpectomy?

Not at all. Often times, the outcomes of a study are emphasized, while the study’s design isn’t clearly articulated. With JAMA, one of the biggest sources of confusion was that it was not clearly explained or emphasized anywhere that patients in this study were not randomly assigned to different treatments all ending up with the same excellent outcomes. Many patients included in this study were advised to undergo particular treatments based on what their doctors felt was the best approach after considering the specifics of their particular case.

For example, often women who have large areas of DCIS in their breasts that would be difficult to remove in a small operation are advised to undergo mastectomy. With mastectomy, a woman with DCIS has an extremely low risk of cancer coming back, and an extremely high likelihood of survival. To assume that you could take this same woman with a large area of cancer, perform a lumpectomy (thereby possibly not removing all the cancer) and expect the same outcome would be completely wrong. And in no way did this study show that this would be reasonable to expect. And there are other mitigating circumstances that may lead us, the surgeons, to advise a woman to have a mastectomy. For example, women with the BRCA gene mutation are at much higher risk for cancer recurrence after lumpectomy, and mastectomy is frequently advised. Yes, for some women both lumpectomy and mastectomy would be associated with equal outcomes in their particular cases, and some of these women choose to have a mastectomy. For these women there are other factors that drive decision making beyond just equal survival rates, and in my experience, the choices my patients make are usually well thought out and made after careful consideration and consultation regarding the risks and benefits of all their options. Â

To reiterate, there is no one-size-fits-all. And this holds true for women with DCIS as much as for any other scenario. So my interpretation of this study? Perhaps one reason why all groups had good outcomes was in part because we, the surgeons, are making reasonably good recommendations as to who should receive which type of surgery, by working with our patients and figuring out the best course on a case-by-case basis.

2) If more extensive surgery and treatment did not lead to better survival does that imply that having no treatment at all (i.e., “watchful waiting”) is equally as acceptable?

Absolutely not. The women included in the JAMA study all underwent treatment of some sort, which ranged from lumpectomy alone, to lumpectomy with radiation, to mastectomy. And with appropriate treatment, excellent outcomes can be expected. The same cannot be said for doing nothing.

The comparison between DCIS and prostate cancer where the watchful waiting approach has been adopted to some extent has been offered up as a model to follow for DCIS patients, but in truth, it is not a good comparison to make for many reasons. First, men with prostate cancer for whom watchful waiting is recommended are often elderly and infirm, with other concomitant illnesses that have a higher likelihood of causing death before their prostate cancer progresses. Second, surgical treatment for prostate cancer, a prostatectomy, is associated with a significantly higher risk of serious operative complications (compared to the operations we perform for breast cancer) and one might think twice before recommending this course of action for someone elderly or infirm. There is no question that we, as breast surgeons, also think twice before recommending extensive or aggressive treatment for our older female patients, especially when they have other co-morbid conditions. But to assume that a 45-year-old otherwise healthy woman would have no progression of her DCIS over the ensuing

40 years (the current lifespan of the average woman in the United States is approximately 85 years old) is potentially dangerous. Equally as concerning is the assumption that if no treatment is given, and disease progresses, there is a guarantee that it can be treated later with no compromise in cure or change in outcome. Progression of DCIS to spread throughout the breast or progression from DCIS to invasive cancer is a potentially catastrophic development that could lead to the need for even more aggressive treatment than what was originally feasible: women who were lumpectomy candidates may now require mastectomy. And women who would not have been recommended to have chemotherapy based on DCIS, may now require it for their invasive cancer.

The point is, watching and waiting involves a little bit of Russian Roulette. And anyone who claims that he/she can be even reasonably sure of equivalent excellent outcomes with the “no treatment” approach has absolutely no basis for making these claims. True, there may be individual cases among the 60,000 women diagnosed with DCIS each year where watching and waiting may be appropriate, where there is no progression, and the disease is stable for years and years. But no one currently has the tools or tests to identify or accurately predict which cases fall into this category. This is an area of extensive research and we welcome the day where we can safely recommend this approach for a real number of patients.

There is another reason why the “no treatment” approach to DCIS is not a great idea, and for some reason, this important fact is never brought up or widely discussed. When an abnormality is identified on a mammogram and a needle biopsy is done and shows “DCIS,” we ultimately remove this area in its entirety (with lumpectomy or mastectomy). When we examine the tissue that was removed at surgery, approximately 10% of the time there will actually be invasive cancer in and around the area of the original biopsy. In other words, the needle biopsy under-estimated and under-sampled the true extent of disease. So if 100 women went untreated for what was “DCIS” on the biopsy, 10 of them would actually be undergoing no treatment for what is actually invasive cancer. In this country, one of the most common cancer-related lawsuits is failure to diagnose or treat breast cancer. The hypocrisy here is undeniable: we can’t advocate for not treating what may be potentially life-threatening cancer on one hand, yet permit lawsuits for failing to diagnose and treat it on the other.

So when discussing the “watching and waiting” approach for DCIS, one very real question that first needs to be answered is, “How do we know for certain that it’s just DCIS?” And the answer is: we don’t. Women considering a “no treatment” approach to DCIS must be made aware of this important caveat.

For the millions of women who have been treated for DCIS and the approximately 60,000 that will be diagnosed this year and the years to come, DCIS is the most curable form of breast cancer with cure rates of approximately 97%, and with the right care, a woman with DCIS has every reason to be optimistic and expect an excellent long-term outcome. Through research, progress has been and will continue to be made, and more and more options will become available. Perhaps one day soon, with research leading the way, we will be able to confidently advise a large proportion of women with DCIS that “no treatment” is a safe and viable option. Believe me, even those of us who make our living by performing breast surgery would welcome that day. But that day is not today.

For now, we who are on the front lines of cancer treatment taking care of women (and men) with breast cancer every day look at each case in detail and work with each person to decide jointly what is best for each particular case. This study reaffirms that the treatment options for DCIS that my colleagues and I recommend and then perform are effective and curative, and this is gratifying to know. And the treatment choices that we and our patients make together are sound and should not be a continued source of anxiety, confusion, and second-guessing.

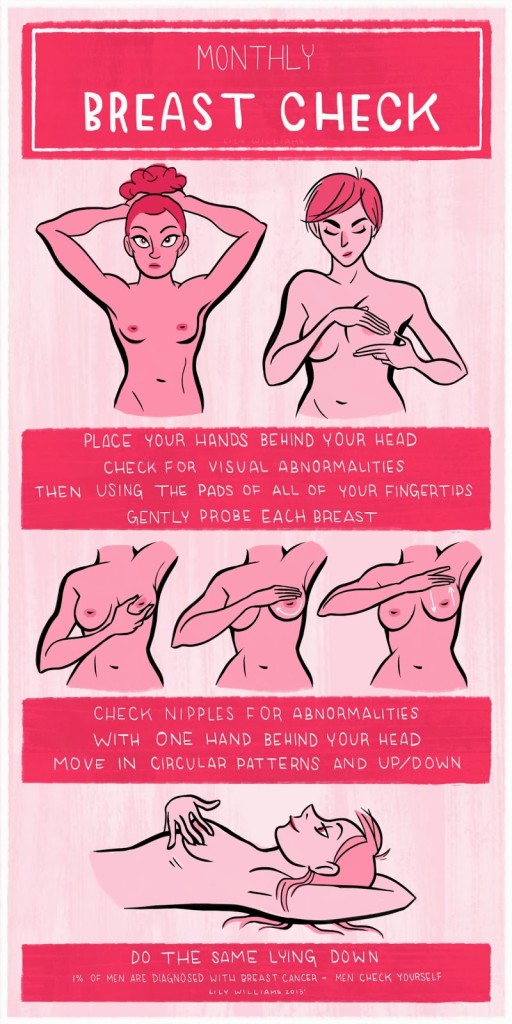

Knowing your body’s “normal” will increase the chance that you would find a new lump that is not normal, and approximately 10-15% of breast cancers are not seen on mammograms. Doctors would never tell a woman (or man!) not to be familiar with what’s normal for any other part of the body, so why stop at breasts- especially when recognizing an unfamiliar lump could alert you to something a mammogram may miss?

Knowing your body’s “normal” will increase the chance that you would find a new lump that is not normal, and approximately 10-15% of breast cancers are not seen on mammograms. Doctors would never tell a woman (or man!) not to be familiar with what’s normal for any other part of the body, so why stop at breasts- especially when recognizing an unfamiliar lump could alert you to something a mammogram may miss?

Fast-forward to today. There is no shortage of information out there if you are newly diagnosed with breast cancer. And it’s really the Internet that has definitely been the game changer, though not always in a good way. The internet, email, and social media have changed the way we do everything on a day to day basis, make travel reservations, communicate, even date (swipe left, swipe right- I have no idea what that even means), and it has definitely changed the world a woman and her family and friends face when she is diagnosed with breast cancer.

Fast-forward to today. There is no shortage of information out there if you are newly diagnosed with breast cancer. And it’s really the Internet that has definitely been the game changer, though not always in a good way. The internet, email, and social media have changed the way we do everything on a day to day basis, make travel reservations, communicate, even date (swipe left, swipe right- I have no idea what that even means), and it has definitely changed the world a woman and her family and friends face when she is diagnosed with breast cancer.

My final goal of writing the book had to do with helping women beyond those that I take care of personally. The

My final goal of writing the book had to do with helping women beyond those that I take care of personally. The